Parkinson’s disease is traditionally associated with neurological damage in the brain, brought on by a drastic drop in dopamine production, but a new study suggests it could get started in an unexpected part of the body: the kidneys.

Led by a team from Wuhan University in China, the study is primarily concerned with the alpha-synuclein (α-Syn) protein, which is closely associated with Parkinson’s. When production goes awry and creates clumps of misfolded proteins, it interferes with brain function.

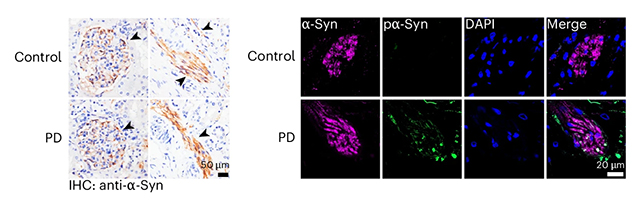

The key discovery here is that α-Syn clumps can build up in the kidneys, as well as the brain. The researchers think these abnormal proteins might actually travel from the kidneys to the brain, possibly playing a part in triggering the disease.

“We demonstrate that the kidney is a peripheral organ that serves as an origin of pathological α-Syn,” write the researchers in their published paper.

There’s a lot to dig into here. The research team ran multiple tests, looking at the behavior of α-Syn in genetically engineered mice, as well as analyzing human tissue – including samples from people with Parkinson’s disease and chronic kidney disease.

The team found abnormal α-Syn growth in the kidneys of 10 out of 11 people with Parkinson’s and other types of dementia related to Lewy bodies (a commonly seen type of α-Syn protein clumping).

That wasn’t all: in another sample batch, similar protein malfunctions were found in 17 out of 20 patients with chronic kidney disease, even though these people had no signs of neurological disorders. This is more evidence that the kidneys are where these harmful proteins begin to gather, before brain damage begins.

The animal tests backed up these hypotheses. Mice with healthy kidneys cleared out injected α-Syn clumps, but in mice with kidneys that weren’t functioning, the proteins built up and eventually spread to the brain. In further tests where the nerves between the brain and kidneys were cut, this spread didn’t happen.

As α-Syn proteins can also move through the blood, the researchers tested this too. They found that a reduction in α-Syn in the blood also meant less damage to the brain, which means this is another consideration to bear in mind.

There are some limitations to this study. The number of people that tissue samples were taken from was relatively small, and while mice make decent stand-ins for humans in scientific research, there’s no guarantee that the exact same processes observed in the animals are happening in people.

However, there are lots of interesting findings here that can be explored further, which could eventually aid in the development of new treatments for Parkinson’s and other related neurological disorders.

The likelihood is that Parkinson’s (in a similar way to Alzheimer’s disease) is actually triggered in a variety of ways and through a variety of risk factors. For example, previous studies have also suggested it could get started in the gut – and now it seems the kidneys could be connected in a similar way.

“Removal of α-Syn from the blood may hinder the progression of Parkinson’s disease, providing new strategies for therapeutic management of Lewy body diseases,” write the researchers.

The research has been published in Nature Neuroscience.

This news item came from: https://www.sciencealert.com/parkinsons-disease-might-not-start-in-the-brain-study-finds