Abstract

The impact of subthalamic nucleus (STN) deep brain stimulation (DBS) on neuropsychiatric fluctuations in Parkinson´s disease (PD) remains unclear. The Neuropsychiatric Fluctuations Scale (NFS) can help to fill this gap, directly measuring fluctuations between the OFF- and ON-medication conditions. The NFS provides NFS-plus (hyperdopaminergic) and NFS-minus (hypodopaminergic) sub-scores. Based on these, the NFS global scores express the overall magnitude of neuropsychiatric symptoms in both the OFF- and ON-medication states. The total fluctuation score (TFS) represents the difference between ON- vs. OFF-medication NFS global scores, thus assessing fluctuations amplitude. The NFS was used to evaluate changes in neuropsychiatric fluctuations between the OFF- and ON-medication conditions before and 1-year after bilateral STN-DBS in 45 PD patients (32 males; mean age, 61.3 ± 7.2 years; PD duration, 10.2 ± 3.0 years). After surgery, the amplitude of neuropsychiatric fluctuations was significantly reduced (p < 0.001), confirming the efficacy of STN-DBS on these symptoms.

Introduction

Parkinson´s disease (PD) is a complex neurodegenerative disorder that often presents with a variety of non-motor symptoms, especially neuropsychiatric symptoms1. People with PD might report anxiety, sadness, fatigue, lack of energy and motivation when they are in the OFF-medication (hypodopaminergic) condition, and euphoria, well-being, impulse control disorders (ICD), hypomania, and psychosis under the ON-medication (hyperdopaminergic) condition2,3. However, neurotransmitters other than dopamine (e.g., serotonin, norepinephrine, acetylcholine, and adenosine) also contribute to various neuropsychiatric states1. Additionally, non-motor symptoms frequently fluctuate3,4 both in parallel with, and independently from, motor fluctuations5.

Identification and treatment of both neuropsychiatric symptoms and fluctuations should be part of the routine patient management6. Several tools are available to detect both non-motor symptoms7,8 and non-motor fluctuations9,10, as well as a behavioral scale for the assessment of mood fluctuations11. However, all these instruments are retrospective, and none enables specific and acute assessment of neuropsychiatric fluctuations. To fill this gap, we developed a self-administered scale, the Neuropsychiatric Fluctuations Scale (NFS), specifically designed to be completed during different acute medication conditions (thus not retrospectively)2. The NFS has been shown to be effective in identifying and quantifying acute neuropsychiatric symptoms in both the OFF- and ON-medication conditions12,13. Moreover, a single administration in patients without neuropsychiatric fluctuations could capture chronic hypo- or hyperdopaminergic state2.

Similar to motor fluctuations, neuropsychiatric fluctuations might respond to oral dopaminergic treatment optimization3,5. Advanced treatments such as subcutaneous apomorphine (APO) and levodopa/carbidopa intestinal gel (LCIG) pumps may be effective for non-motor symptoms, but they have not been specifically investigated for the treatment of neuropsychiatric fluctuations14. Bilateral subthalamic nucleus (STN) deep brain stimulation (DBS) can also effectively reduce the overall burden of non-motor symptoms15. Post-operative improvement of health-related quality of life was notably correlated to the improvement of neuropsychiatric symptoms such as mood problems, apathy, attention, and memory changes16. Furthermore, STN-DBS has been reported to reduce neuropsychiatric fluctuations17, likely even better than the best medical therapy alone18. However, all these results are based on retrospective data, thus with possible related biases.

The main objective of the present study was to acutely assess the impact of STN-DBS on neuropsychiatric fluctuations in people with PD using the NFS before and 1 year after surgery.

Results

A total of 48 PD patients were included in the study. One patient could not complete the NFS under the ON-medication condition prior to surgery (spell of discomfort), and data were missing in the OFF-medication condition one year after surgery in two patients for technical reasons. Table 1 shows the main demographic and clinical characteristics before and after STN-DBS for the 45 patients with complete data set.

Results are given as mean ± SD. At 1-year after surgery, there was a significant improvement in the MDS-UPDRS part III score in the OFF-medication/ON-stimulation condition, in the MDS-UPDRS parts I, II, and IV scores in the ON-medication/ON-stimulation condition, and in the ASBPD compared to before surgery (Table 1). On the contrary, there was a worsening of the Frontal Score after surgery (Table 1). The reduction of LEDD (about 52%) was also significant.

Primary outcome

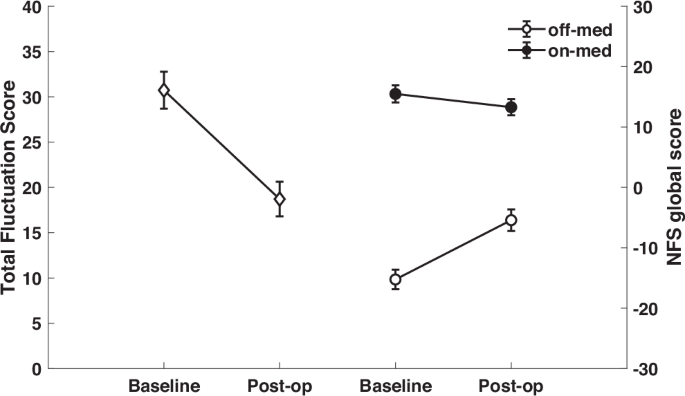

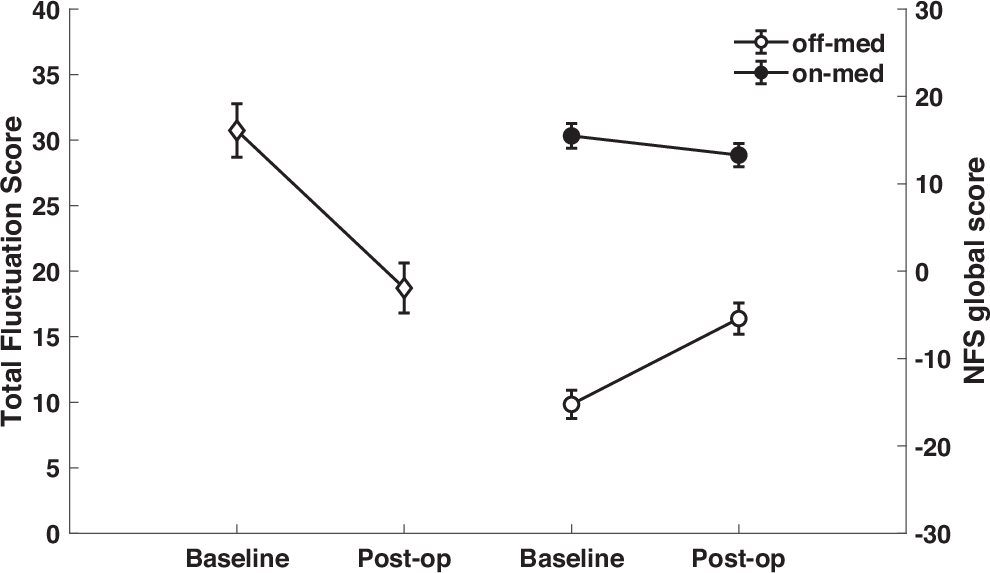

Neuropsychiatric fluctuations as measured by the TFS were significantly reduced after surgery (30.7 ± 13.7 before surgery vs. 18.7 ± 12.8 one year after surgery; t = 6.22; p < 0.001). As can be seen in Fig. 1, the amplitude of the fluctuations, i.e., the difference in the NFS global scores between the ON- and OFF-medication conditions, was greater before surgery than after surgery.

Secondary outcomes

The effects of both Medication (p < 0.001) and Time point (p = 0.003) on the NFS-global score were significant, as was the interaction between the two factors (p < 0.001). The NFS-global score decreased under medication, and also decreased after compared to before surgery. Examination of the interaction showed that the reduction in the NFS-global score one year after surgery compared to before surgery was significant only in the OFF-medication condition (OFF-medication: −15.24 ± 10.77 vs. −5.42 ± 12.02; p < 0.001; ON-medication: 15.49 ± 9.43 vs. 13.29 ± 8.93; p = 0.158) (Fig. 1).

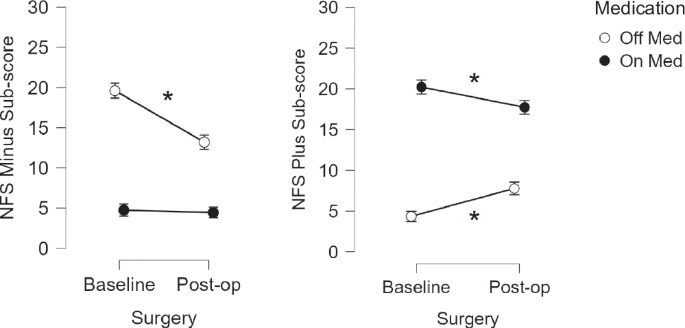

Comparison of the NFS sub-scores revealed a significant decrease in the NFS-minus sub-score one year after surgery compared to baseline in the OFF-medication state only (p < 0.001). Regarding the NFS-plus sub-score, it was significantly increased after surgery compared to before in the OFF-medication condition (p = 0.001), and significantly decreased in the ON-medication condition (p = 0.013) (Fig. 2).

A significant correlation was found between the NFS-global score and the MDS-UPDRS part III score in the OFF-medication condition before surgery (rho = −0.572; p < 0.001), but not at 1-year follow-up (r = −0.105; p = 0.490).

The correlation between the NFS-global score and the MDS-UPDRS IV score in the OFF-medication condition was significant before (rho = −0.407; p = 0.006) but not after surgery (rho = −0.246; p = 0.103).

There was no correlation between the change in the TFS and the change in LEDD (r = 0.233; p = 0.123) after surgery. Moreover, at 1-year follow-up, there were no correlations between the NFS-plus sub-score in the ON-medication condition and LEDD (r = 0.075, p < 0.624), the change in LEDD (r = 0.070, p < 0.647), and the percent reduction of LEDD (r = 0.093, p < 0.543).

Discussion

Using a specifically designed scale, the NFS, in a well-defined cohort of 45 PD patients, we found a beneficial effect of bilateral STN-DBS on reducing neuropsychiatric fluctuations at 1-year after surgery. Indeed, there was a significant reduction of the NFS-global score in the OFF-medication condition, and a marginal one in the ON-medication condition, leading to a 42% reduction of neuropsychiatric fluctuations one year after surgery.

As already shown in previous large randomized trials19,20, the scores of all the MDS-UPDRS parts improved after surgery, except for the motor score in the ON-medication condition which remained stable despite a significant reduction of LEDD.

Regarding correlation analyses, the significant negative correlation between the NFS-global score and the MDS-UPDRS parts III and IV existing in the OFF-medication condition at baseline, was no longer present one year after surgery. Finally, the change in TFS was not linked to the change in LEDD.

This is one of the few studies acutely assessing the impact of STN-DBS on neuropsychiatric fluctuations using a specific neuropsychiatric scale. Over the past few years, research has been mostly focused on non-motor symptoms or non-motor fluctuations in general15,21,22. A recent combined retrospective-prospective controlled study15 did not find significant improvement in neuropsychiatric symptoms when comparing PD patients treated with STN-DBS to patients treated with best medical treatment at 3-year follow-up. However, to assess non-motor symptoms the authors used the retrospective Non-Motor Symptoms Scale (NMSS)23 which includes only two neuropsychiatric symptoms, namely mood/apathy and perceptual problems/hallucinations. Moreover, the study did not specifically address non-motor fluctuations.

Few data are available about the specific effect of STN-DBS on neuropsychiatric fluctuations17,18,24. In an earlier study that prospectively investigated behavior in 63 PD patients before and 1-year after bilateral STN-DBS using the ASBPD, we reported improvement in mood fluctuations in both the OFF-medication and ON-medication states24. More recently, using again the ASBPD in 69 PD patients with at least 6-year follow-up after STN-DBS, we found a significant improvement on neuropsychiatric fluctuations (namely for euphoria and dysphoria) compared to baseline17. However, the ASBPD is a retrospective hetero-assessment using a semi-structured interview, and it has been shown that hetero-assessments are less reliable than self-questionnaires7. In addition, the ASBPD has only two items for neuropsychiatric fluctuations: ON-medication euphoria and OFF-medication dysphoria. Therefore, the positive outcomes of these studies were awaiting additional support regarding neuropsychiatric fluctuations. In a cohort of 20 PD patients with STN-DBS, another group reported some benefit in non-motor fluctuations, including psychiatric fluctuations, only in the OFF-medication condition at 2-year follow-up22. The authors used a custom-made retrospective questionnaire (based on the one previously used by Witjas et al. 25) that consisted of 25 items across four categories, including psychiatric symptoms, and they also created a scale to record the severity of non-motor fluctuations.

Compared to the above studies, our findings are specific to neuropsychiatric fluctuations, and they are not biased by the retrospective nature of the scale used to assess the outcomes. This point is critical especially considering that significant changes in cognitive tests are frequently found after surgery26. Indeed, worsening in attention and memory can impact the reliability of recalling symptoms.

The improvement of the neuropsychiatric fluctuations after surgery is likely at least partly linked not only to the improvement of motor function but also to the decrease of motor complications. Indeed, the correlation between the NFS-global score and the MDS-UPDRS part III and part IV scores in the OFF-medication condition observed at baseline were no longer significant one year after surgery. Moreover, changes in the LEDD after surgery were not linked to the changes of neuropsychiatric fluctuations. These findings are intriguing and suggest a key role of STN stimulation in modulating neuropsychological symptoms and fluctuations. Indeed, the direct impact of STN stimulation on specific non-motor symptoms in acute and long-term setting is known27. The pathophysiological bases of non-motor symptoms are related to the disruption of different neurotransmitter systems (notably dopamine, but also other systems) due to PD neurodegeneration28, and it is hypothesized that symptom-specific neural network changes play an important role29. DBS can alleviate or aggravate neuropsychiatric symptoms via modulating the non-motor parts of the STN, current spreading to neighboring areas, or modulating the basal ganglia-thalamo-cortical loops29.

Interestingly, contrary to what occurred in the OFF-medication condition, we did not find a significant improvement in the NFS-global score after surgery in the ON-medication condition. Thus, our study suggests that STN-DBS reduces neuropsychiatric fluctuations between the two medication conditions mainly through the reduction of hypodopaminergic symptoms in the OFF-medication condition, whereas there is a more limited reduction of the hyperdopaminergic symptoms in the ON-medication condition. Indeed, the observed reduction in the NFS-plus sub-score at follow-up could be due to the reduction of dopaminergic treatment rather than to a direct effect of STN-DBS. We did not find any correlation between LEDD reduction and NFS-plus sub-score in ON-medication after surgery. In other words, the remarkable LEDD reduction allowed by surgery can be translated into reduced hyperdopaminergic sub-scores, i.e., a normalization of the neuropsychiatric state of patients, rather than a deficit in compensation of dopa-responsive symptoms. However, we cannot exclude a possible impact of the stimulating contact of the DBS lead, since the effects of STN-DBS on different non-motor symptoms has been reported to be linked to the stimulation of STN sub-regions (e.g., with better effect on apathy with the electrode placed more ventrally to the STN and worse effect with the usual dorsolateral placement)29.

Our study also showed a temporal connection between motor function and neuropsychiatric state in the OFF-medication condition at baseline, as already shown in earlier research12,30. These findings can be explained by the hypodopaminergic background of these two entities31. However, this bond was lost after the surgery as discussed above.

Our study has some limitations. First, the sample size is limited. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of DBS surgeries was greatly reduced in our center, with the cancellation of all non-vital surgeries, preventing inclusion of a greater number of patients in the present study. Second, the NFS is rather a new scale. However, results using the NFS have already been published2,12,32, including a pre-validation study13. Moreover, the NFS has been designed to quantify the overall neuropsychiatric symptoms and to measure their fluctuations between different medication states. As such, it cannot be used to distinguish different symptoms individually.

To conclude, this study has allowed to unveil the specific impact of STN-DBS on neuropsychiatric fluctuations. Previous studies were scarce and unspecific, especially because the lack of tools enabling to detect these fluctuations accurately and acutely. Here, we have used the NFS, a specific non-retrospective scale, to directly measure neuropsychiatric fluctuations, as well as neuropsychiatric symptoms in both ON- and OFF-medication conditions. We have shown that bilateral STN-DBS effectively reduces neuropsychiatric fluctuations.

The NFS promises to be a useful tool not only in the research settings, but also in the practical clinical work.

Methods

Population

Consecutive patients with PD (according to the criteria proposed by the International Movement Disorders Society, MDS)33 who received STN-DBS (using the previously described criteria)34 at the Movement Disorders Center of the Grenoble Alpes University Hospital (Grenoble, France) between 2016 and 2021 were included.

Inclusion criteria were bilateral STN-DBS surgery, and the preoperative and 1-year postoperative completion of the NFS. Exclusion criteria were patients with diagnosis other than PD, and patients with unilateral STN-DBS or different DBS targets.

The local ethical committee approved the study (NCT04608123). All patients gave their informed consent.

Assessments

All included patients underwent preoperative and 1-year postoperative standardized neurological and neuropsychiatric evaluations.

Neurological assessment included the MDS Unified Parkinson´s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) for rating cognitive and psychiatric symptoms (part I), activities of daily living (part II), motor symptoms of PD (part III), and motor complications (part IV)35.

Neuropsychiatric fluctuations were assessed using the NFS2. Briefly, the NFS consists of 20 items: ten NFS-plus and ten NFS-minus items, corresponding to neuropsychiatric symptoms usually linked to hyperdopaminergic and hypodopaminergic states, respectively.

The NFS provides two sub-scores, a NFS-plus sub-score corresponding to positive (or hyperdopaminergic) symptoms, and a NFS-minus sub-score corresponding to negative (or hypodopaminergic) symptoms, each with a maximum of 30 points. The NFS global score is calculated by subtracting the NFS-plus sub-score from the NFS-minus sub-score, thus ranging from −30 to +30. The more negative the score, the more the patient experiences hypodopaminergic symptoms. Conversely, the more positive it is, the more the patient experiences hyperdopaminergic symptoms. Importantly, the NFS allows to directly assess the amplitude of the fluctuations between the OFF- and ON-medication conditions, using a total fluctuation score (TFS). The TFS is calculated by subtracting the NFS-global score obtained under the ON-medication condition from the NFS-global score measured during the OFF-medication condition (NFS-global ON – NFS-global OFF), ranging from 0 to 60. The closer to 60, the greater the amplitude of the fluctuations between the two medication conditions.

Neuropsychiatric evaluation also included the following tests: the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) for assessing depression, the Starkstein Apathy Scale (SAS) for assessing apathy, the neuropsychiatric fluctuations part of the Ardouin Scale of Behaviour in PD (ASBPD) for evaluating ON-state euphoria and OFF-state dysphoria36, the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale (MDRS-2) and the Frontal Score for comprehensive evaluation of cognition.

Before surgery, both the MDS-UPDRS part III and the NFS were completed in the “defined-OFF” (at least twelve hours after receiving the last dopaminergic treatment dose), and in the “defined-ON” conditions (about 45–60 min after an acute levodopa challenge) conditions37. At 1-year follow-up, the two scales were administered in both the OFF-medication and ON-medication conditions, and with stimulation ON (with the chronic parameters of stimulation).

The total daily levodopa equivalent dose (LEDD) was calculated for all the patients before and after surgery38.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze data regarding demography and disease duration, dopaminergic medication, and assessment results. Continuous variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation ( ± SD). Differences in the MDS-UPDRS parts I-IV, the BDI-II, the SAS, the ASBPD, the MDRS-2, the Frontal Score, and the LEDD between before and after surgery were analyzed using parametric tests (paired t-test) for normally distributed data, and non-parametric tests (Wilcoxon) otherwise.

The primary outcome was the difference in the TFS between before and one year after surgery, assessed using a paired-sample T-test. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Secondary outcomes were: 1) the difference in the: a) NFS-global score and b) NFS-minus and NFS-plus sub-scores between before and 1 year after surgery, in both the OFF-and ON-medication conditions. Scores were compared using a 2 (Medication, OFF vs. ON) x 2 (Time point, pre-surgery vs. one year after surgery) repeated measures ANOVA. Interactions between the two factors were examined using Holm post-hoc tests; 2) the correlations between the NFS-global score and: a) the MDS-UPDRS part III score in the OFF-medication condition before and 1 year after surgery; b) the MDS-UPDRS part IV score (motor complications) in the OFF-medication condition before and 1 year after surgery; 3) the correlation between the change in the TFS score and the change in LEDD at 1-year follow-up; 4) the correlation between the NFS-plus sub-score in the ON-medication condition, the absolute LEDD, and the change in LEDD at 1-year follow-up.

The assumption of normality was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Pearson’s correlations were computed for normally distributed data and Spearman´s rank-order correlations were computed for not-normally distributed ones. For all statistical analyses, p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Statistical analyses were performed using JASP (version 0.15; JASP team 2021, University of Amsterdam).

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

-

Weintraub, D. et al. The neuropsychiatry of Parkinson’s disease: advances and challenges. Lancet Neurol. 21, 89–102 (2022).

-

Schmitt, E. et al. The Neuropsychiatric Fluctuations Scale for Parkinson’s Disease: A Pilot Study. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 5, 265–272 (2018).

-

Martínez-Fernández, R., Schmitt, E., Martinez-Martin, P. & Krack, P. The hidden sister of motor fluctuations in Parkinson’s disease: A review on nonmotor fluctuations. Mov. Disord. 31, 1080–1094 (2016).

-

Storch, A. et al. Nonmotor fluctuations in Parkinson disease: Severity and correlation with motor complications. Neurology 80, 800–809 (2013).

-

Classen, J. et al. Nonmotor fluctuations: phenotypes, pathophysiology, management, and open issues. J. Neural Transm. 124, 1029–1036 (2017).

-

Seppi, K. et al. Update on treatments for nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease—an evidence‐based medicine review. Mov. Disord. 34, 180–198 (2019).

-

Stacy, M. et al. Identification of motor and nonmotor wearing-off in Parkinson’s disease: Comparison of a patient questionnaire versus a clinician assessment. Mov. Disord. 20, 726–733 (2005).

-

Chaudhuri, K. R. et al. The movement disorder society nonmotor rating scale: Initial validation study. Mov. Disord. 35, 116–133 (2020).

-

Ossig, C. et al. Assessment of Nonmotor Fluctuations Using a Diary in Advanced Parkinson’s disease. J. Parkinsons. Dis. 6, 597–607 (2016).

-

Kleiner, G. et al. Non-Motor Fluctuations in Parkinson’s Disease: Validation of the Non-Motor Fluctuation Assessment Questionnaire. Mov. Disord. 36, 1392–1400 (2021).

-

Rieu, I. et al. International validation of a behavioral scale in Parkinson’s disease without dementia. Mov. Disord. 30, 705–713 (2015).

-

Del Prete, E. et al. Do neuropsychiatric fluctuations temporally match motor fluctuations in Parkinson’s disease? Neurol. Sci. 43, 3641–3647 (2022).

-

Schmitt, E. et al. Fluctuations in Parkinson’s disease and personalized medicine: bridging the gap with the neuropsychiatric fluctuation scale. Front. Neurol. 14, 1–9 (2023).

-

Dafsari, H. S. et al. EuroInf 2: Subthalamic stimulation, apomorphine, and levodopa infusion in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 34, 353–365 (2019).

-

Jost, S. T. et al. A prospective, controlled study of non-motor effects of subthalamic stimulation in Parkinson’s disease: Results at the 36-month follow-up. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 91, 687–694 (2020).

-

Jost, S. T. et al. Non-motor predictors of 36-month quality of life after subthalamic stimulation in Parkinson disease. npj Park. Dis. 7, 48 (2021).

-

Abbes, M. et al. Subthalamic stimulation and neuropsychiatric symptoms in Parkinson’s disease: Results from a long-term follow-up cohort study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 89, 836–843 (2018).

-

Lhommée, E. et al. Behavioural outcomes of subthalamic stimulation and medical therapy versus medical therapy alone for Parkinson’s disease with early motor complications (EARLYSTIM trial): secondary analysis of an open-label randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 17, 223–231 (2018).

-

Deuschl, G. et al. A Randomized Trial of Deep-Brain Stimulation for Parkinson’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 355, 896–908 (2006).

-

Weaver, F. M. et al. Bilateral deep brain stimulation vs best medical therapy for patients with advanced Parkinson disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 301, 63–73 (2009).

-

Dafsari, H. S. et al. Nonmotor symptoms evolution during 24 months of bilateral subthalamic stimulation in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 33, 421–430 (2018).

-

Ortega-Cubero, S. et al. Effect of deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus on non-motor fluctuations in Parkinson’s disease: Two-year’ follow-up. Park. Relat. Disord. 19, 543–547 (2013).

-

Chaudhuri, K. R. et al. The metric properties of a novel non-motor symptoms scale for Parkinson’s disease: Results from an international pilot study. Mov. Disord. 22, 1901–1911 (2007).

-

Lhommée, E. et al. Subthalamic stimulation in Parkinson’s disease: Restoring the balance of motivated behaviours. Brain 135, 1463–1477 (2012).

-

Witjas, T. et al. Effects of chronic subthalamic stimulation on nonmotor fluctuations in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 22, 1729–1734 (2007).

-

Cernera, S., Okun, M. S. & Gunduz, A. A Review of Cognitive Outcomes Across Movement Disorder Patients Undergoing Deep Brain Stimulation. Front. Neurol. 10, 419 (2019).

-

Castrioto, A., Lhommée, E., Moro, E. & Krack, P. Mood and behavioural effects of subthalamic stimulation in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 13, 287–305 (2014).

-

Schapira, A. H. V., Chaudhuri, K. R. & Jenner, P. Non-motor features of Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 18, 435–450 (2017).

-

Petry-Schmelzer, J. N. et al. Non-motor outcomes depend on location of neurostimulation in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 142, 3592–3604 (2019).

-

Ossig, C. et al. Timing and Kinetics of Nonmotor Fluctuations in Advanced Parkinson’s Disease. J. Parkinsons. Dis. 7, 325–330 (2017).

-

Chaudhuri, K. R. & Schapira, A. H. Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease: dopaminergic pathophysiology and treatment. Lancet Neurol. 8, 464–474 (2009).

-

Magalhães, A. D. et al. Subthalamic stimulation has acute psychotropic effects and improves neuropsychiatric fluctuations in Parkinson’s disease. BMJ Neurol. Open 6, e000524 (2024).

-

Postuma, R. B. et al. MDS clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 30, 1591–1601 (2015).

-

Krack, P. et al. Five-Year Follow-up of Bilateral Stimulation of the Subthalamic Nucleus in Advanced Parkinson’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 349, 1925–1934 (2003).

-

Goetz, C. G. et al. Movement Disorder Society-Sponsored Revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): Scale presentation and clinimetric testing results. Mov. Disord. 23, 2129–2170 (2008).

-

Ardouin, C. et al. Évaluation des troubles comportementaux hyper- et hypodopaminergiques dans la maladie de Parkinson. Rev. Neurol. (Paris) 165, 845–856 (2009).

-

Saranza, G. & Lang, A. E. Levodopa challenge test: indications, protocol, and guide. J. Neurol. 268, 3135–3143 (2021).

-

Tomlinson, C. L. et al. Systematic review of levodopa dose equivalency reporting in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 25, 2649–2653 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all PD patients for giving their consent to use their medical data. The authors also thank Paul Krack and Pablo Martinez-Martin for their contribution to the development of the preliminary version of the Neuropsychiatric Fluctuation Scale (not used in this study). This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mari Muldmaa – data acquisition and interpretation, preparing of the first draft, critical revision of the draft, final approval of the completed version, accountability for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Emmanuelle Schmitt – data analysis and interpretation, critical revision of the draft, final approval of the completed version, accountability for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Roberto Infante – data acquisition, critical revision of the draft, final approval of the completed version, accountability for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Andrea Kistner – data acquisition, critical revision of the draft, final approval of the completed version, accountability for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Valérie Fraix – data acquisition, critical revision of the draft, final approval of the completed version, accountability for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Anna Castrioto – data acquisition, critical revision of the draft, final approval of the completed version, accountability for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Sara Meoni – data acquisition, critical revision of the draft, final approval of the completed version, accountability for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Pierre Pélissier – data acquisition, critical revision of the draft, final approval of the completed version, accountability for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Bettina Debû – data analysis and interpretation, critical revision of the draft, final approval of the completed version, accountability for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Elena Moro – study concept and design, data interpretation, critical revision of the draft, final approval of the completed version, accountability for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

E.M. is an associated editor of npj Parkinson´s Disease. E.M. has received honoraria from Medtronic for consulting services. She has also received restricted research grants from the Grenoble Alpes University, France Parkinson, IPSEN and Abbott. M.M., E.S., R.I., A.K., V.F., A.C., S.M., P.P., & B.D. have nothing to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Muldmaa, M., Schmitt, E., Infante, R. et al. Deciphering the effects of STN DBS on neuropsychiatric fluctuations in Parkinson’s disease. npj Parkinsons Dis. 10, 205 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-024-00811-1

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-024-00811-1

This was shown first on: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41531-024-00811-1