A landmark UK study reveals that South Asian and Black patients with Parkinson’s suffer worse symptoms, even with equal access to care, spotlighting urgent gaps in diagnosis and support for diverse communities.

Study: The East London Parkinson’s disease project – a case-control study of Parkinson’s Disease in a diverse population. Image Credit: Kotcha K / Shutterstock

Study: The East London Parkinson’s disease project – a case-control study of Parkinson’s Disease in a diverse population. Image Credit: Kotcha K / Shutterstock

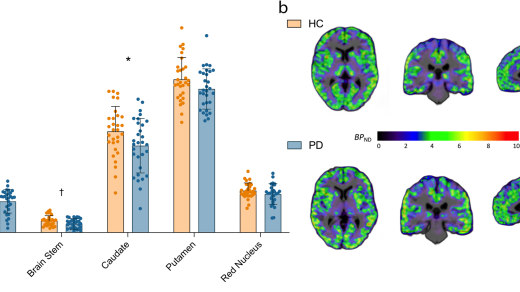

In a recent study published in the journal npj Parkinson’s Disease, researchers utilized data from the East London Parkinson’s Disease project to compare Parkinson’s Disease (PD) clinical outcomes across the UK’s diverse ethnic backgrounds. Study findings revealed that South Asian and Black PD patients performed significantly worse in motor score evaluations than their White counterparts.

Cognitive impairment was similarly substantially more prevalent in minority patients (75% Black, 73% South Asian) compared to White ones (45%). While there was weak evidence that South Asian patients had a slightly earlier age of symptom onset, the time from symptom onset to diagnosis was found to be similar across all groups. These findings highlight the urgent need for policy reforms for more inclusive neuroscience research and suggest that factors beyond diagnostic access may be driving these disparities in underrepresented populations.

Background

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder best known for its progressive exacerbation of motor symptoms, including tremors, rigidity, and slowed movement. However, PD is also associated with a wide range of non-motor complications, such as cognitive impairment.

Decades of clinical and genetic studies have contributed much to the scientific understanding of PD outcomes and genetic predispositions. Recent technological advancements, including next-generation multiomics tools and artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted statistical models, have progressed our understanding of PD pathophysiology by leaps and bounds.

Unfortunately, most of what we know about the disease comes from studies involving predominantly White, Western European populations. These populations are genetically distinct and typically more affluent and educated than South Asian, Black, and other ethnic minorities.

The absence of ethnically diverse cohorts has left crucial questions unanswered: Does PD manifest differently in underrepresented groups? Are patients from racial minorities more severely affected or simply diagnosed, and therefore treated later? As modern medicine allows the global population to age, understanding how Parkinson’s unfolds across different racial and cultural contexts is vital for research accuracy and for building a healthcare system that serves all patients equitably.

About the Study

The present study leverages data from the East London Parkinson’s Disease project, one of the UK’s most ethnically diverse urban population cohorts, to elucidate differences in age at diagnosis and clinical PD outcomes between White, South Asian, and Black ethnic groups. The study employed a case-control design and collected data across multiple community health services and National Health Service (NHS) clinics between 2019 and 2024.

Participants included in the study were classified as ‘cases’ (MDS 2015 confirmed PD diagnosis) or ‘controls’ (age-matched volunteers without a medical history of neurological illness). Collected data included demographic information (age, sex, ethnicity, and education status), medical history (including PD diagnoses and treatments), and economic variables.

Clinical assessments were conducted using previously validated and standardized diagnostic tools, such as the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS), to evaluate motor function. Cognitive performance was assessed via memory, attention, and executive function tests, primarily using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA).

Between-group comparisons were made using T-tests, χ2 tests, Mann-Whitney U tests, and Fisher’s exact tests. Logistic regression models were leveraged to identify the strengths of clinical PD outcomes. All models were adjusted for confounding demographic, medical, and socioeconomic variables, especially age, gender, and disease duration.

Study findings