I suppose it was the end of a delusion: struggling home to the south coast from London by train after a Sunday morning TV appearance reviewing the newspapers on GB News, I opened X on my phone. I realised that viewers had spotted the symptoms of my Parkinson’s disease. I thought I’d been hiding it from the world, but the game was up.

I was no longer in control — my body had betrayed me. On social media, they were pitiless: I rocked back and forward in my seat; I was awkward and hard to watch; I was clearly drunk; I appeared to be under the influence of cocaine; I was, to sum it up, a “twitchy twat”.

I watched it back. I was relieved that the nasty words were — surprise, surprise — gross exaggerations. But there was some jumpiness and a tendency to rock in my seat. I’d been focused on doing a good job; it hadn’t occurred to me that my body was telling a different, far more personal story.

• John Stapleton: ‘I saw the signs I had Parkinson’s’

Parkinson’s is a progressive neurological disorder, a brain disease that gets worse. The condition develops when nerve cells in a small, deep part of the brain called the substantia nigra become damaged and die. These cells are responsible for producing dopamine, a crucial neurotransmitter that helps control and co-ordinate movement. The resulting drop in dopamine slows movement, affects dexterity and causes tremors. The primary treatment, levodopa, is converted into dopamine to replenish the diminished supply. Over time, however, it stops working, while the condition progresses through its increasingly bleak stages.

I know that those horrors await me but, as far as I’m concerned, my condition has remained stable since my diagnosis four years ago, when I was 52. But I’m facing a brutal new reality: the disease is progressing. It is more visible and noticeable than I realised, and all my private protestations that I was in control of my Parkinson’s are dust. From now on, it will be in the driving seat, not me.

Amid redundancy, my symptoms developed rapidly

The years before I was diagnosed were some of the busiest, best and, ultimately, most bruising years of my life. My career was in the stratosphere: first the editor of The Andrew Marr Show and then, three years later, head of BBC political programmes. I had two young children and then, very quickly, lost both parents. Everything was stressful, but I managed to ride it out and stay somehow fine.

Then came Covid. Don’t worry, I won’t bore you with it — I can’t remember much of it anyway. But things blinked back on again in early 2021 when I returned to the office and was presented with a round of BBC cuts, which, it quickly became clear, would include me. Within days I was toast: I said goodbye to my team on Zoom and that was that. No kind words, no thanks, no leaving do. Nothing.

The depth of the shock, anger and sadness is hard to overstate. The BBC was part of my identity, perhaps unhealthily so, and to have it ripped away so brutally plunged me into a kind of grief. It was in that context, just days away from my official departure date from the BBC, that I rapidly started to develop symptoms. My partner, Holly, noticed I couldn’t lift my feet up when I walked; my right arm hung lifeless and numb; I began to feel a tremor.

Rob Burley at the finish line of a charity walk in aid of Parkinson’s in 2024, and, below, the day before the trek ended

ROB BURLEY/INSTAGRAM

“When I tried to walk, I shuffled like an old man”

ROB BURLEY/INSTAGRAM

I tend to talk about difficult things rather than sweep them under the carpet, but it was different with Parkinson’s. My GP was worried, but she didn’t say the P-word, and that was all right with me. I’d need to see a neurologist, but I’d have to wait for at least a year. Maybe, with some rest, it might die down on its own, I thought. A few days later, it let rip. The tremor on my right side became full-blown shaking. When I tried to walk, I shuffled like an old man. I had no medication that could touch it. I was frightened. It was time to go to A&E. There, finally, a doctor said the word. Almost. “I’m worried about Parkinsonian symptoms,” she said. That made two of us. I’d started reading up on it and my symptoms were classic.

And then, a reprieve. The next morning, a supremely confident consultant, full of chummy bonhomie, arrived with a couple of student doctors and the result of the scans I’d had the night before. All smiles, he told me there was nothing to be concerned about. There was no sign of a brain haemorrhage or a tumour. There’d be a follow-up appointment with a neurologist to get to the bottom of this soon, he said, but right now I was “all clear”. I was elated. As far as I was concerned, this was a clean bill of health. He hadn’t even mentioned Parkinson’s, despite it being the most obvious explanation, so I took “all clear” to mean just that.

• A-ha singer Morten Harket reveals he has Parkinson’s disease

A few days later, I arrived in the department of neurology in a dilapidated hospital wing in Haywards Heath, West Sussex. Having had Parkinson’s ruled out, I was still concerned but wasn’t particularly worried. So I sat in the waiting room for an hour, watching patients come and go. Some shuffled, some had a visible tremor, and all were older than I was. This wasn’t where I belonged.

“Robert Burley?”

I followed the doctor into an office of old furniture, peeling paintwork and, it turned out, no preamble.

“Mr Burley,” she said once she was sure I’d sat down, “you have Parkinson’s.”

The rest of the conversation has been obliterated by shock. I can’t remember a word. It was as if the doctor had taken me out with a swift cosh to the back of the neck, dragged me out of the building and dumped me on the grass verge outside. That was where I came to. I then called Holly and wondered how I was going to drive home. When I did, the steering wheel felt enormous, alien and impossible to manoeuvre. I crawled home into my new life, in the slow lane, scared to death.

And so began my “Parkinson’s journey”: from the moment of diagnosis, you are in permanent motion on a slow-moving vehicle, something like the lawnmower in David Lynch’s The Straight Story, inching your way towards a terrifying yet distant destination.

The bucket list is a matter for today now

Everything you’ve told yourself about how your life will play out is junked when you’re diagnosed in your early fifties. The bucket list is a matter for today, when you don’t know whether you’ll be able to board a plane ten years from now. The possibility of enjoying life a little more for a couple of decades and working a lot less starts to fade. You realise you can’t afford not to keep working at full pelt because you don’t know when you’ll have to stop altogether. And what if you need round-the-clock care? How will you pay for that?

• Parkinson’s disease: the game-changing future of early diagnosis

Then you upgrade your ride, from lawnmower to Lamborghini, and before you know it, you’re heading at speed towards your final destination. That’s where my mind goes in the depths of the night, depths I am increasingly familiar with because Parkinson’s robs me of sleep. The dread is not death — that’s waiting for all of us — but the possibility of some sort of existence that is worse than dying. Unable to speak, unable to enjoy, an object — almost literally — that cannot look after itself. Given all the uncertainties of the condition, this seems like the most likely outcome.

It’s hard enough trying to survive in the media when you’re over 50 without announcing that you have an old man’s disease. Scared of being written off, I kept it a secret for about a year, only telling friends, family and Andrew Marr. We’d left the BBC at about the same time and reunited to launch his new show on LBC. Andrew understood — he’d nearly died in 2013 after a devastating stroke — and it was a good job, because I was a bit of a mess.

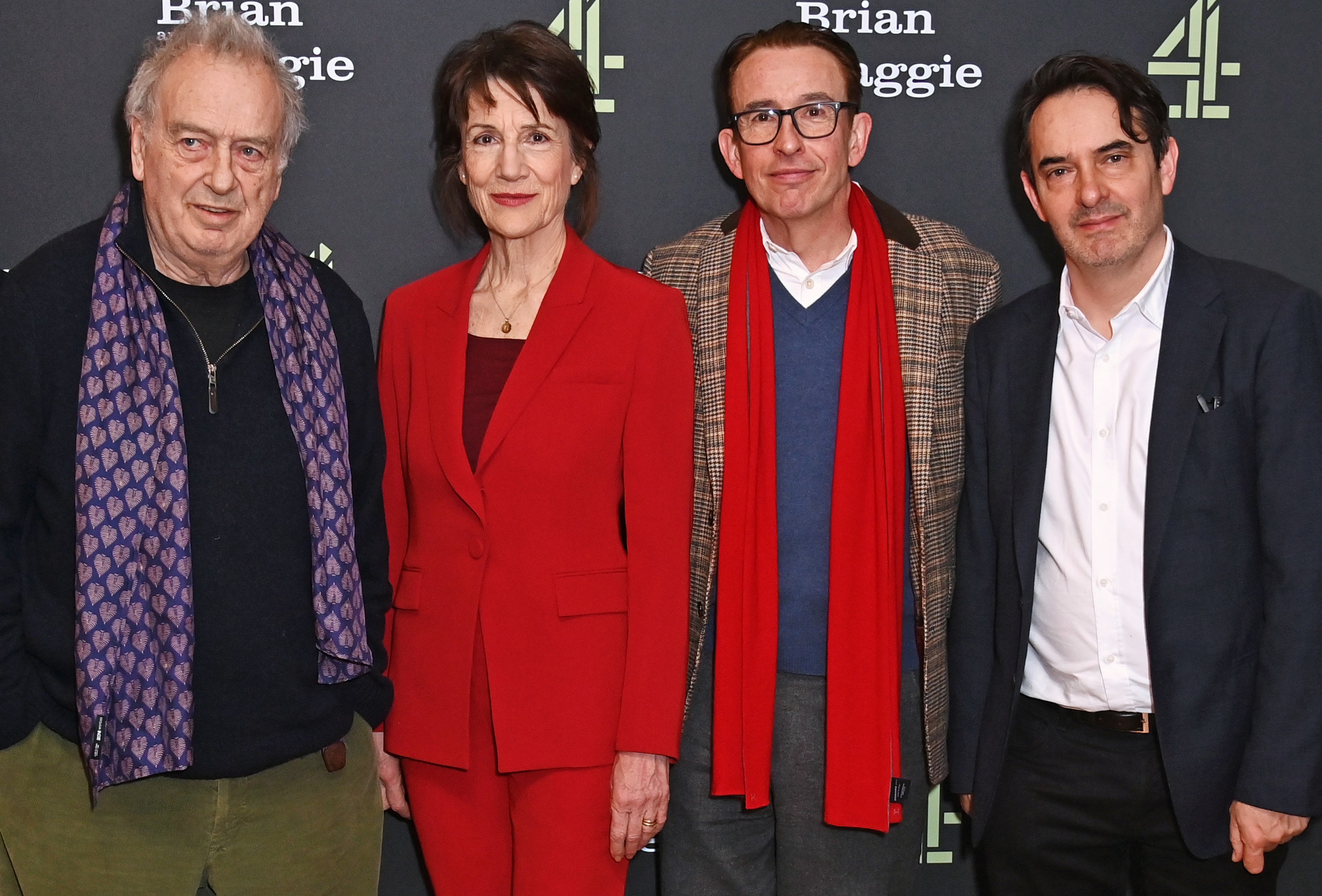

Attending the London screening in January for the TV drama Brian and Maggie with, from left, director Stephen Frears and stars Harriet Walter and Steve Coogan — Burley wrote the book on which it was based

WIREIMAGE

The problem was that while Parkinson’s drugs do work, they also make it worse at the same time. Treating the classic slow movement and shuffling gait — known as bradykinesia — with levodopa can produce a side-effect of jerky, involuntary movements known as dyskinesia. It was this side-effect that was visible on GB News, not the original symptom.

The most serious issue in those early days was exhaustion. Insomnia goes with the territory, so I was used to daytime naps, but once “the meds” kicked in, I’d find myself dropping off in meetings and never feeling anything much better than awful. The only bright spot was the effectiveness of fast-acting levodopa at keeping me moving and managing the tremor. Then, one weekend, I woke to find myself slumped against a wall on the pavement at a street party near my home. Piecing it together, the last thing I remembered was taking my usual dose just a few minutes before passing out. This made sense of similar episodes at work when I’d been knocked out flat in the middle of the day. The levodopa was the problem. It wasn’t long after that, as I moved on to jobs at Sky and now Times Radio, that I decided that keeping my condition secret from employers and the world was an unhealthy and untenable choice.

The hallucinations typically come at night

Perhaps the worst feature of Parkinson’s is hallucinations. Typically, they come at night. The lights will buzz on and off before the room transforms into a sinister fairground or an industrial wasteland. The air will swarm with flies or wasps. The sensation that the bed is being lifted up and is heading inexorably toward the window is real, but this isn’t Bedknobs and Broomsticks. Instead, consumed with dread, I am desperate to break the spell but cannot shout or scream. It’s usually then that Holly or my eldest boy, Noah, will arrive, woken by the cries for help and urgent exclamations like, “I cannot speak!” that I have, in fact, managed to scream into the night. Shaken out of it, I emerge from each episode exhausted and scared.

After a few years, this starts to wear you down. The unpredictable and insidious nature of the condition dominates family life. The exhaustion never really lets up. As a result, after school, when your youngest begs you to play football, you have to say no or else agree to go to the park and then give up after ten minutes. The ruined nights start to affect your partner, and it becomes impossible to avoid exile to the melancholy cell otherwise known as the spare room.

Meanwhile, the drugs start to feel less effective and require adjustment. New ones are introduced in new combinations. These require even closer monitoring and assessment. And you realise then — in my case, with the help of GB News viewers — that of course this thing is progressing and may soon start running away from you.

But there is an upside: I have become more creative, more driven and perhaps even more authentically myself than I was before that afternoon in Haywards Heath. Why? A diagnosis like that changes you. The clock starts ticking, You become much more interested in the now than the tomorrow that never comes. Procrastination is a thing of the past, priorities are reordered and laziness is no longer a problem. I am writing two novels, finishing a non-fiction book and have ideas for a TV drama and a stage play. They may never happen, but it won’t be for want of trying.

Some people on the drugs gamble or shop excessively

That’s the psychology. The rest is chemistry: the drugs counteract the depletion of dopamine, which causes the classic symptoms associated with movement. But there’s a complication: dopamine is also associated with motivation, risk-taking, reward, pleasure, impulsivity, novelty-seeking and creativity. So stimulating dopamine can affect your behaviour.

This is why there are so many stories of patients who discover a hitherto unknown artistic gift after they are diagnosed and on medication. But this is also where things get dark again. There is a class of Parkinson’s drugs known as dopamine agonists that can trigger “impulse control disorders”: people gamble, shop excessively, eat compulsively or engage in hypersexual behaviour. I confess this happened to me, but my experience was minor and transitory: I went online and bet some cash on the roulette wheel and lost. I closed the account. I then started overspending on music software — not quite as shocking as hypersexuality, but as rock’n’roll as I get these days. After that it eased, and I was left with creative renewal and powerful drive — a big bonus after being dealt such a brutal hand.

• I’m a fashion editor in my 40s — Parkinson’s means I can’t trust my own body

To have Parkinson’s is to be isolated. The minute you are diagnosed, you are on a different track from everyone else you know. It changes everything, from the big life and death stuff to the small and tedious details. As I write, it’s the morning, usually my most productive time, but today my fingers don’t work; they tingle with what I think of as Parky’s pins and needles. It feels as if I’m typing in a weird pair of malfunctioning electric gloves, my day sabotaged by my inner old man. I don’t know anyone else who knows how that feels.

There are so many ways in which I’ve been changed by Parkinson’s, not because of the pain or the side-effects of the drugs, but much more profoundly because of the experience. Writing this took me back to that grass verge in Haywards Heath where I absorbed the shock of the diagnosis. The journey since has been slow, surprising and sometimes scary.

I’m not on that verge any more. I’ve come a long way. I picture myself now standing alone on a rock in a cove somewhere in England. The tide is rushing in and there is no way out. I am isolated and frightened, yet I feel more firmly myself than ever before. So here I am, a weak swimmer, about to drown.

What was that I said about an upside?

It is that after Parkinson’s, anything seems possible. Who’s to say I can’t make a swim for it and survive?

This was shown first on: https://www.thetimes.com/life-style/health-fitness/article/rob-burley-parkinsons-disease-xd0gb909w