Oral bacteria that migrate to the gut can generate metabolites that reach the brain and accelerate Parkinson’s disease.

Here is one more reason to brush your teeth carefully every day. Researchers in Korea have found strong evidence that bacteria from the mouth can take hold in the gut, influence neurons in the brain, and may help set off Parkinson’s disease.

Parkinson’s disease is a widespread neurological condition marked by tremors, muscle stiffness, and slowed movement. It affects roughly 1 to 2 percent of people over the age of 65, making it one of the most common brain disorders associated with aging.

Earlier research had shown that the gut microbiome of people with Parkinson’s differs from that of healthy individuals, but which microbes were involved and how they influenced the disease was not well understood.

A specific bacterium and metabolite stand out

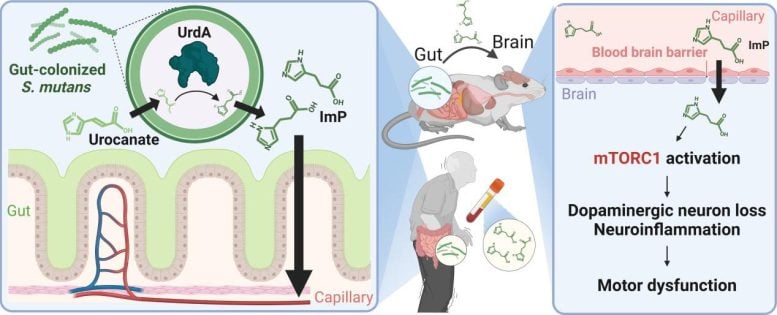

New findings help clarify that connection. Researchers discovered that people with Parkinson’s had elevated levels of Streptococcus mutans, a bacterium typically associated with tooth decay, within their gut microbiomes. Once established in the gut, this bacterium produces an enzyme called urocanate reductase (UrdA) and a metabolic byproduct known as imidazole propionate (ImP).

Both substances were found at higher concentrations in the gut and bloodstream of patients. The evidence suggests that ImP can circulate through the body, reach the brain, and contribute to the loss of dopamine-producing neurons.

The research behind these discoveries was conducted by a collaborative team led by Professor Ara Koh and doctoral candidate Hyunji Park from POSTECH’s Department of Life Sciences. They worked alongside Professor Yunjong Lee and doctoral candidate Jiwon Cheon from Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, as well as Professor Han-Joon Kim from Seoul National University College of Medicine.

Together, the team identified how chemical byproducts released by oral bacteria after colonizing the gut could play a role in triggering Parkinson’s disease. Their findings were recently published in Nature Communications.

Using mouse models, the researchers introduced S. mutans into the gut or engineered E. coli to express UrdA. As a result, the mice showed elevated ImP levels in blood and brain tissue, along with the hallmark features of Parkinson’s symptoms: loss of dopaminergic neurons, heightened neuroinflammation, impaired motor function, and increased aggregation of alpha-synuclein, a protein central to disease progression.

A signaling pathway links microbes to neurons

Further experiments demonstrated that these effects depend on the activation of the signaling protein complex mTORC1. Treating mice with an mTORC1 inhibitor significantly reduced neuroinflammation, neuronal loss, and alpha-synuclein aggregation, and motor dysfunction. This suggests that targeting the oral–gut microbiome and its metabolites may offer new therapeutic strategies for Parkinson’s disease.

“Our study provides a mechanistic understanding of how oral microbes in the gut can influence the brain and contribute to the development of Parkinson’s disease,” said Professor Ara Koh. “It highlights the potential of targeting the gut microbiota as a therapeutic strategy, offering a new direction for Parkinson’s treatment.”

Reference: “Gut microbial production of imidazole propionate drives Parkinson’s pathologies” by Hyunji Park, Jiwon Cheon, Hyojung Kim, Jihye kim, Jihyun Kim, Jeong-Yong Shin, Hyojin Kim, Gaeun Ryu, In Young Chung, Ji Hun Kim, Doeun Kim, Zhidong Zhang, Hao Wu, Katharina R. Beck, Fredrik Bäckhed, Han-Joon Kim, Yunjong Lee and Ara Koh, 5 September 2025, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-63473-4

The research was supported by the Samsung Research Funding & Incubation Center of Samsung Electronics, the Mid-Career Researcher Program of the Ministry of Science and ICT, the Microbiome Core Research Support Center, and the Biomedical Technology Development Program.

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.