Design

This study was a single-center, home-based, randomized controlled trial comparing HPT with TR. Approval for the trial protocol was obtained from the Medical Ethical Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital (NO.JS-2648). All assessments were conducted at the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Beijing. The intervention in both groups took place in the patients’ homes under the in-person supervision of a physical therapist or via remote supervision.

Participants

Participants were recruited from the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Beijing. The eligibility criteria for participation in this study included patients with mild to moderate Parkinson’s disease (Hoehn and Yahr stages I ~ III) who met the diagnostic criteria for primary PD as outlined by the Movement Disorder Society Clinical Diagnostic Criteria [14]. Eligible participants were required to be between the ages of 60 and 80 and had not participated in any exercise programme for the past 4 weeks. And the patients should have good mobile phone usage skills, provide informed consent, and voluntarily participate in this study.The exclusion criteria included individuals who were diagnosed with parkinsonism, other severe nervous system or motor system diseases, significant cognitive or mental disorders, or severe visual or hearing impairment or who demonstrated poor compliance.

Eligibility was established through screening followed by in-person assessments. During telephone screening, a trained research assistant interviewed the patients regarding their age, physical activity, medication use, ability to complete questionnaires or perform app tasks, and facility at home and availability (Supplementary file1). Then, participants were invited to the outpatient clinic for additional face-to-face screening. This face-to-face screening was conducted by a physiatrist who recorded patients’ medical history and assessed PD severity. If there was no reason for exclusion at this stage, patients were asked to participate in motor function and quality of life assessments. All patients provided written informed consent at the beginning of the assessment.

Eligible patients were randomly assigned to either the HPT group or the TR group using computer-generated random numbers. Following randomization, patients were solely informed about the content of their allocated program by their therapists, remaining unaware of the intervention content in the other group. Details of both programs were not disclosed, except for the similarities shared by both groups, such as coaching, a motivational app, and home-based exercise five times per week. Both programs were tailored based on the patients’ assessment scores to ensure that all eligible patients could complete the program. Researchers responsible for assessing outcomes or analysing data were blinded to group allocation.

Intervention

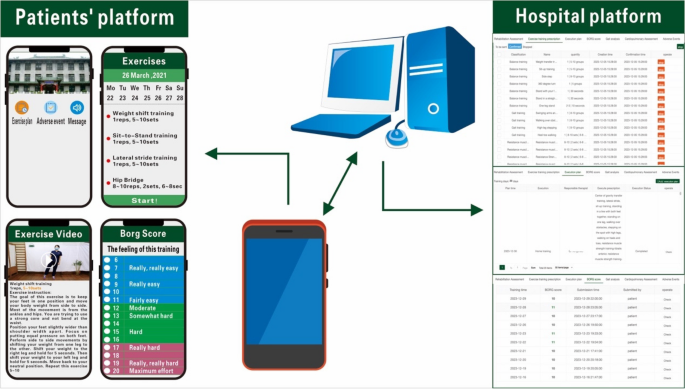

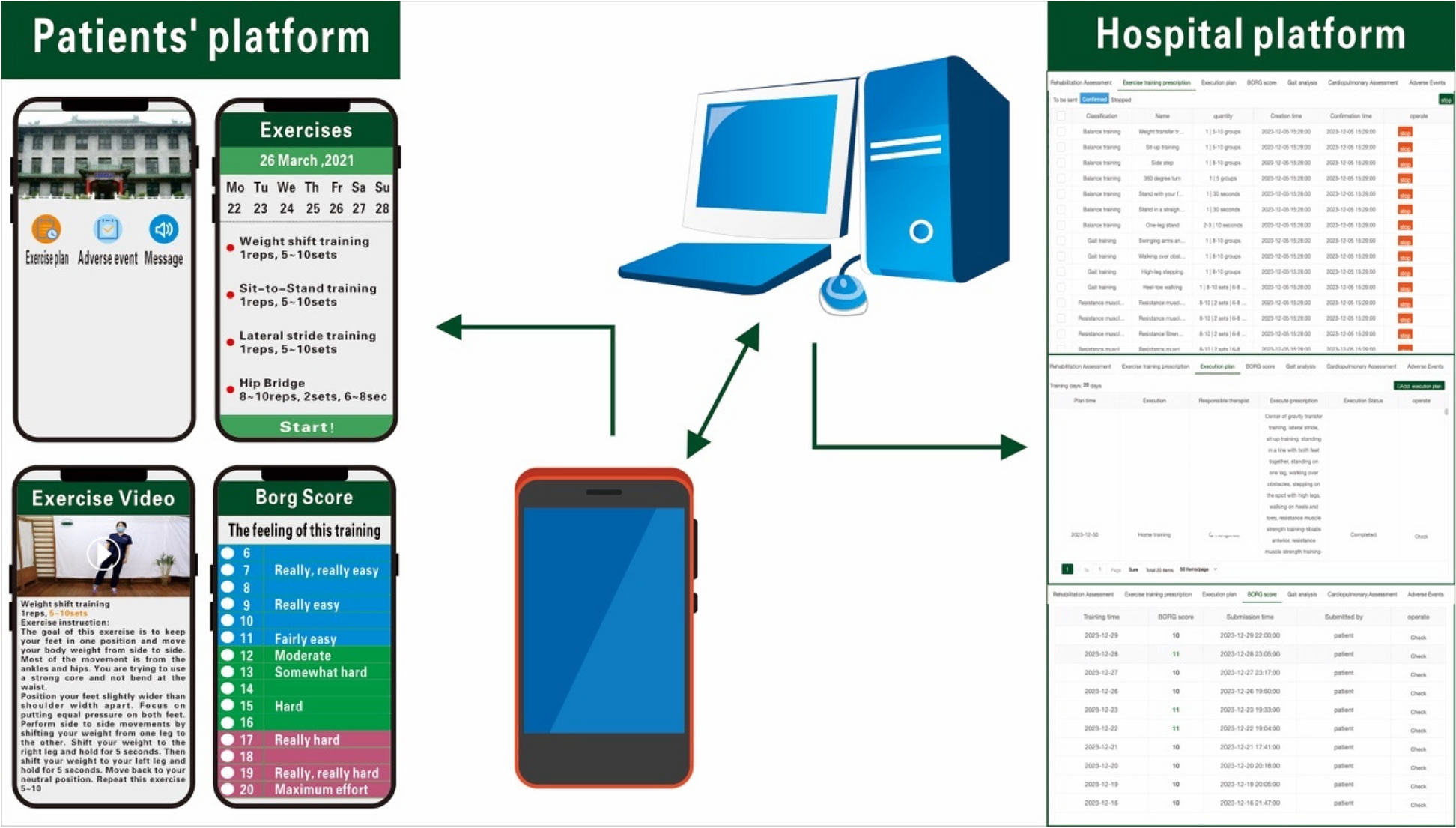

Both groups received regular rehabilitation training [15], including balance training, resistance muscle strength exercise, gait training (e.g., LSVT BIG), stretching exercise, and aerobic exercise (e.g., walking and cycling). Low to moderate intensity exercise was employed, with patients self-perceiving their level of exertion graded using the Borg scale (scores ranging from 6 to 20) and maintained within the range of 11 to 14 points. The total exercise duration for each session was 40–60 min, and the exercise was conducted five times per week and was consistently maintained over a consecutive four-week period. The physiatrist adjusted the exercise programme once a week, progressively increasing the intensity and difficulty of the exercises. The HPT group received rehabilitation services at home three times a week, with an additional two sessions performed independently based on the home exercise assignments provided by their physical therapist. Licensed therapists received uniform training and were assigned to subjects’ homes for physical therapy according to the principle of proximity to the patient’s home address.The TR group was instructed to exercise under the guidance of a mobile application (Fig. 1). The subjects were educated to use the app on their cell phones. The caregivers could supervise, and we recommended it to prevent adverse events. Both groups of patients received a dedicated mobile app tailored to provide identical features, including patient information, training plans, instructions, tips, training movement demonstration videos, and a platform for submitting adverse events. Once patients reported adverse events, they received assistance from their physiatrists, and their physiatrists adjusted the subsequent training plans. Patients contacted the therapists or physiatrists with any questions, and therapists provided reminders for patients to complete their daily exercise plans. The daily exercise plan is indicated in Table 1.

Outcome measures

The baseline and outcome measures were assessed by a rater who was not involved in either the allocation or implementation of the intervention. Measurements were taken in the clinical setting to standardize the assessment. At baseline, individuals were weighed, and their BMI (Body Mass Index) and clinical characteristics were recorded via clinical interviews and medical history. The primary outcome was the between-group difference in the motor section score of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS3). The secondary outcomes included between-group differences in the Berg Balance Scale (BBS), Timed Up-and-Go test (TUG), Five Times Sit-to-Stand test (FTSST), Freezing of Gait Questionnaire (FOGQ), gait cycle parameters, muscle strength, and Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire-39 (PDQ-39) scores. All tests were performed in a standardized state.

Primary outcome

-

Motor examination

The Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS), well validated clinical rating scale, is widely regarded as the “gold standard” for assessing the severity of patients’ symptoms in PD patients [16]. The UPDRS3 comprises 18 items designed to evaluate the severity of motor symptoms associated with PD [17].

Secondary outcomes

-

Balance function

The 14-item Berg Balance Scale is commonly utilized to assess the extent of postural instability during both static and functional mobility tasks, as well as to predict the risk of falling [11]. For PwPD, the minimal clinically important difference for the BBS has been reported to be approximately 4 to 6 points [18].

-

Risk of fall

The TUG and FTSST are objective measurement tools that can be used to predict the risk of falling and functional performance. During the TUG [19], participants stood up from a chair, walked 3 m at their usual safe walking speed, turned around, and returned to a seated position. A proposed cut-off score of 11.5 s was suggested for discriminating between PwPD who did and did not fall [20]. In the FTSST [21], participants rose from a chair and returned to the seated position as quickly as possible for five repetitions, with their arms folded across their chests during the test. Patients could rest for one minute before and after the test to ensure that they were in their optimal state. The proposed cut-off score for discrimination between PwPD who did and did not fall was 16.0 s [22].

-

Muscle strength

Lower limb muscle strength was assessed using isokinetic dynamometry (ISOMOVE, Tecnobody Company, Italy) according to a standardized protocol [23]. The isokinetic variables of knee extension peak torque (EPT, Nm), extension total power (ETP, W), and extension average torque (EAT, Nm) and knee flexion peak torque (FPT, Nm), flexion total power (FTP, W), and flexion average torque (FAT, Nm) were measured and recorded for analysis purposes.

The Freezing of Gait Questionnaire (FOGQ), comprising six questions, is the most widely used patient-reported outcome measure for assessing Freezing of Gait (FOG). The FOGQ-CH showed good reliability and validity for assessing PwPD in China [24]. The step length (m), step velocity (m/s), preswing angle (degree), ground impact, pulling acceleration (G) and swing power (G) were all evaluated by an IDEEA activity monitor (Minisun, Fresno, CA). Participants completed four flat 10-m walking trials with the device on as required [25].

The UPDRS2 consists of 13 items specifically crafted to assess the activities of daily living through self-reports provided by the PwPD [26].

-

Quality of life

The Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire-39 (PDQ-39), which measures quality of life in 8 domains with 39 questions, is based on patient self-perception and a reliable and valid instrument [27].

-

Adverse event

Patients were instructed to promptly report any adverse events directly to their assigned physical therapist. Adverse events noted during training sessions, as well as those with any conceivable connection to the exercises performed, were deemed potentially related.

Data analysis

Our study was powered to show a comparative effect of HPT and TR on UPDRS3 scores after 4 weeks. The following thresholds were used to calculate the UPDRS3 score: 2.5, denoting minimal difference; 5.2, denoting moderate difference; and 10.8, denoting substantial clinical difference [28]. We combined these data with unpublished data from our previous feasibility study in which a between-group difference of 2 points was observed at our site. We utilized the standard deviation (SD) from our previous study (3.5 points), and our power calculation was our planned analysis method. In total, a sample size of 63 patients per group was determined to achieve 80% power, accounting for an attrition rate of 18–20%.

Data analysis was conducted on an intention-to-treat basis for patients who completed the assessment, regardless of whether they completed the assigned intervention. Descriptive statistics were employed to summarize the demographics, motor function, and quality of life of the participants at each time point. Means (SD) were used for continuous variables, and frequencies (%) were used for categorical variables. The normality of variables was assessed using the skewness statistic and a normal probability plot. All participants were examined at baseline and after 4 weeks for changes in balance function, lower extremity muscle strength, gait, independence of activities of daily living (ADL) and quality of life (QOL). Student’s t test and the Mann‒Whitney U test were used to assess the differential changes in the primary and secondary outcome variables between the 2 groups at 4 weeks compared with baseline for both outcomes. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS statistical software, version 25.0 (IBM Corporation). All the statistical tests were two-tailed with a 5% level of statistical significance.

Get the source article here